Sonic tourism in San Francisco

I’m really intrigued by the idea of sonic tourism — going to places to experience the acoustic landscape there. There have been a few efforts to document sound destinations, including the wonderful Sound Tourism, but nothing that feels comprehensive.

There are at least a few kinds of sonic tourism spots, and some of the impressive ones weren’t conceived of as destinations at all. Teufelsberg in Berlin, for example, is a giant echo chamber. Common sounds take on an otherworldly quality as they bounce off the walls. I’d love to visit the world’s quietest anechoic chamber at Orfield Labs in Minnesota. And otherwise impressive sights, like the regular movements of enormous bat colonies in Austin, are really incredible for the sound they produce.

In San Francisco, though, there are a few places especially geared towards listeners. The Wave Organ, an acoustic sculpture by the Exploratorium on the bay, is one such location. It’s a beautiful little stone structure out on the jetty with a network of Seussian pipes running from under the waves up to various listening stations. The rumbles and gurgles of the incoming tides are amplified and distorted as they get routed up to the listeners. I made this recording during a visit:

Another spot in the Bay Area is the 92-foot-tall aeolian harp in South San Francisco. Aeolian harps are passive instruments played by the movement of the wind, and this one’s on a hill with a great view of the Bay. I haven’t yet been, but I’m looking forward to it. Is there another city in the world that has two major acoustic sculptures like these?

Add to that that San Francisco is the home of Audium, the world’s only “theater of sound-sculptured space,” and San Francisco seems like a global leader for sonic tourism. I’d be interested in finding more spots to visit, here and elsewhere.

Site redesign

If you fall into the intersection of people who have looked at this website before yesterday and people who are looking at it after today, you may notice that I’ve given it a bit of a spitshine.

It’s still on WordPress, but in place of the venerable DePo Skinny theme, it’s now using a custom theme that I built on top of the Thematic framework. The most notable differences are that I’ve pushed all of the margins outward, made all the text bigger, and pulled the information from the bottom up to a new sidebar. My 1-column days are over.

Also, I’ve used my favorite color as the hover for all of the links.

I had made and modified WordPress themes before, but I was surprised to discover how long it has been. I’d never, for example, used a “Child Theme,” which appear to have been state-of-the-art since, like, 2009. There’s a bit of a conceptual learning curve, but using one you can develop a whole theme basically only using CSS with only touches of basically copy-and-paste PHP. In addition to the WordPress Codex entry, I found the ThemeShaper tutorial really helpful.

One note about responsive design: I don’t have it. I was conflicted about that, and the next redesign may support it, but I wanted to get something finished and it seems like smartphones do pretty well with reflowing the content.

I’ll probably work out some of the kinks over the next couple of days, but if you find something that seems unusual, please let me know.

Conversation’s just fine, thanks: a response to Sherry Turkle

Every once in a while, my Iron Blogger group decides to take on a common topic. At our meet-up this week, a handful of us agreed to take on last week’s Sherry Turkle op-ed in the New York Times. It’s called “The Flight from Conversation,” and it seems to cover some of the same territory as her book “Alone Together”: namely, that we’re allowing gadgets to get in the way of interpersonal communication, favoring “sips” of online contact over a “big gulp of real conversation.”

I disagree with Turkle on both her premise and its conclusion. I’m just not convinced that the anecdotes she collects amount to more than the kind of bogus trend story NY Times is notorious for. Worse, it has the particular flavor of a moral panic, where the issue raised threatens to disrupt the social order. But just as teen texting, comic books, Dungeons and Dragons, rock and roll, and many others failed to unravel the threads of society, we may just make it through the “handheld gadget” era.

In fact, of course, the sort of conversations we have today are the result of refinement over thousands of years, and it would require extraordinary evidence to support the extraordinary claim that this latest change is different in kind and the one that will finally undo us.

And really, the examples Turkle cites don’t seem new. Quiet offices, 16-year-old boys who wish they knew how to hold a conversation, high school students who don’t want to speak with their parents about dating — are these really the products of mobile devices, or the way things always have been? Am I mistaken to think that a high school sophomore in 1952 would have wanted an alternative to asking his father for dating advice, even if he couldn’t characterize it as a sophisticated AI?

More importantly, though, I object to the idea that the inclusion of technology in conversation makes it any less “real,” or even less good. Certain kinds of conversations seem less likely, like those between passengers on a bus or elevator, or, say, patients in a waiting room. But — and I don’t mean to be flip here — so what? These aren’t the “big gulp” conversation Turkle’s concerned with. What’s more, they seem institutionally biased towards extroverts.

I will grant, though, that I’ve seen plenty of occasions where somebody has been rude or anti-social with a device in hand. But they’re rude because they’re violating social norms and expectations, not because those specific norms and expectations are fixed and unchanging. To the extent that gadgets affect our conversations, communities need to evaluate their own experiences, and come to their own conclusions. At South by Southwest this year, for example, I was very comfortable using my phones at meals or in conversations, because that was the community norm there. Turkle’s model doesn’t seem to account for that.

She does get close though, with the suggestion that certain physical spaces or times are gadget-free. I like that suggestion, even if I disagree with the reasoning that drives it. Coming up with a smart way to manage our relationships so that people don’t feel neglected doesn’t require throwing away the smartphone, it just requires being sensitive and respectful to what people expect, gadgets or otherwise.

The impossibility of imagining information retrieval in the past

It’s harder to imagine the past that went away than it is to imagine the future. What we were prior to our latest batch of technology is, in a way, unknowable. It would be harder to accurately imagine what New York City was like the day before the advent of broadcast television than to imagine what it will be like after life-size broadcast holography comes online. But actually the New York without the television is more mysterious, because we’ve already been there and nobody paid any attention. That world is gone.

My great-grandfather was born into a world where there was no recorded music. It’s very, very difficult to conceive of a world in which there is no possibility of audio recording at all. Some people were extremely upset by the first Edison recordings. It nauseated them, terrified them. It sounded like the devil, they said, this evil unnatural technology that offered the potential of hearing the dead speak. We don’t think about that when we’re driving somewhere and turn on the radio. We take it for granted.

–William Gibson, interviewed in the Paris Review no. 211

There’s a whole class of information that’s both trivially easy for Web-literate people to access today and virtually impossible to access with tools from even 10 or 15 years ago.

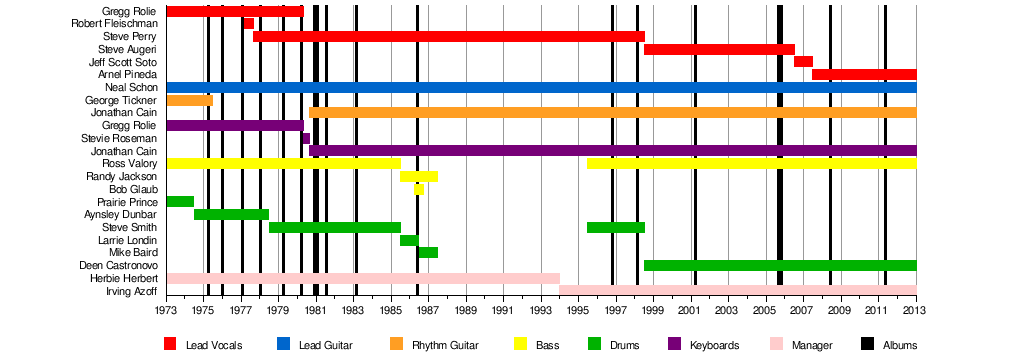

I’ve thought about this fact for a while, and one of my favorite examples has been the names of members of a band. It’s one Google or Wikipedia search away, but as Gibson suggests above, I almost cannot conceive of how to determine this without those tools.

Seriously: what could you do? Such information would not likely be in an encyclopedia, and maybe not in any printed reference books. You could ask at a record store, or call a radio station or the label they were on (after finding a number on the back of an LP, in a catalog, or calling an operator in the city in which they were based).

I’d used that example to describe the phenomenon for a long time before finding one of my favorite sections of the Wikipedia, a timeline of the members of Journey, ((It’s also dynamically generated with a plug-in called Timeline, which makes it semantically significant and editable. It’s a pretty incredible thing.)) embedded teeny-tiny here:

The difference is incredible. And it’s easier (for me at least) to imagine getting this information through an augmented reality pop-up or piped into a heads-up display than to get it in any analog way.